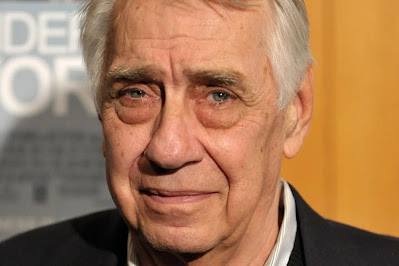

Ahead of “Seinfeld’s” final episode in May 1998, Entertainment Weekly published a Definitive Viewer’s Guide, including a rundown of various celebrities’ favorite episodes. Paul Thomas Anderson, who directed Hall in three films, cited “The Library,” though he didn’t call it that, he called it “The one with Philip Baker Hall.” Why was it his favorite? “Because Hall,” Anderson explained, “is the greatest American ever.” I have been thinking about that proclamation ever since. I assume PTA just responded to EW’s inquiry by AOL email that with that one sentence, negating any follow-up questions, but boy, aren’t you just desperate to hear Anderson’s definition of “the greatest American ever.” Then again, perhaps the answer was there in that unforgettable face, a rugged, mountainous visage with craggy lines that seemed to have been dynamited and then carefully carved, Gutzon Borglum-style, deep bags under his eyes emitting a weariness that can only come from having already seen it all. And that voice. Hall was born in Toledo in 1939, and went to college there, and the Google tells me there is such a thing as an Inland North accent prone to Toledoans, but I don’t know. Hall’s voice seemed more all-American, by which I don’t mean wholesomeness or industriousness, but a gravelly honesty, the kind of born of fatigue with the way things are and yet a lingering desire to tell you the way it is.

You heard it during his single, crucial scene in “Say Anything” (1989). Playing the IRS investigator who exposes his Jim Court’s (John Mahoney) tax evasion, he plays his character’s meeting with Jim’s daughter Diane (Ione Skye) not annoyed but gentle, understanding, if painfully forthright. In his direct line readings (“but he’s guilty”), he simply opens Diane’s eyes to the truth, both small and large. He unlocked a different kind of truth in “Secret Honor” (1984) by playing one of the least great Americans ever (or maybe one of the most American, in his way, Americans ever) – President Richard M. Nixon. Directed by Robert Altman, “Secret Honor” was no biopic and Hall’s performance, as he himself said, was no impersonation. Set almost entirely within one room, the direction made it feel as if the walls were closing in but Hall did too, exhaustingly evincing the sort of man you believed spoke to portraits on the wall, brought down by his extreme self-loathing and incredible self-regard, yet also cultivating a strange sympathy, laying bare a drunken, sweaty, shattered mess of a man.

Hall had a long career, both after and before the 90s, frequently working on the stage, citing a different American President, JFK, as responsible for his career in the form of the American Repertory Company. But it is difficult not to pinpoint his three collaborations with Paul Thomas Anderson in the mid-to-late 90s as his film career’s seismic events. Deeming Hall as a Dietrich or a Mifune to PTA’s von Sternberg or Kurosawa might be laying it on thick, but the duo still made for a fairly extraordinary pair. Indeed, leave it to PTA to watch Martin Brest’s “Midnight Run” (1988) and fixate not on Grodin nor DeNiro nor even Dennis Farina as a mob moss but the mob moss’s advisor associate, Sydney, played by Hall. Come to think of it, maybe that’s what Anderson meant by greatest American, the other guy, the one giving sound advice that goes unheeded.

A year later Hall was featured in PTA’s “Boogie Nights” as an adult film theater impresario who views videotape as the future rather than film much to the consternation of self-professed filmmaker Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds). There, Hall adopted a different voice, giving it a showy kick, not an accent exactly but putting on vocal airs, a venture capitalist as a Megachurch pastor, or something, improbably embodying America’s original recipe of manifest destiny, bean counting, and flimflam. Their final collaboration came at the end of the millennium in the massive “Magnolia,” where Hall’s familiar veracity was fittingly turned inside-out ahead of this so-far upside-down new century. Hall is Jimmy Gator, host of a kids quiz show, a delicious irony in so much as he is a man who literally has all the answers in his hand and none for the wreckage of his life. One part of a complicated mosaic, his storyline finds his public persona finally crumbling under the weight of his private one, brought home in a scene where Jimmy suffers a brief psychological break as he rambles on and on, collapsing on live TV, a wrenching evocation of a man who emotionally no longer has any place left to hide.

Anderson’s “Hard Eight” was originally titled “Sydney,” revealing it as a vehicle for Hall, where in taking a couple stone cold losers (John C. Reilly, Gwyneth Paltrow) under his wing in Reno, his professional gambler demonstrates that “human beings,” to quote Charlie Pierce writing about a different Nevada icon Jerry Tarkanian, “can be the longest shot on the board.” The real experience of “Hard Eight,” however, was in watching Hall go about his business just as the thrill of so many Humphrey Bogart movies was watching Bogey go about his business. “From hotel room to casino to restaurant booth to his car,” Richard T. Jameson wrote in purple prose that was no less apropos for Film Comment, “(Sydney) makes his Nevada rounds like a Flying Dutchman without an opera; just to watch him walk among the gaming tables, his gait even, imperturbable, is one of the privileged moments of the cinema.”

A year later Hall was featured in PTA’s “Boogie Nights” as an adult film theater impresario who views videotape as the future rather than film much to the consternation of self-professed filmmaker Jack Horner (Burt Reynolds). There, Hall adopted a different voice, giving it a showy kick, not an accent exactly but putting on vocal airs, a venture capitalist as a Megachurch pastor, or something, improbably embodying America’s original recipe of manifest destiny, bean counting, and flimflam. Their final collaboration came at the end of the millennium in the massive “Magnolia,” where Hall’s familiar veracity was fittingly turned inside-out ahead of this so-far upside-down new century. Hall is Jimmy Gator, host of a kids quiz show, a delicious irony in so much as he is a man who literally has all the answers in his hand and none for the wreckage of his life. One part of a complicated mosaic, his storyline finds his public persona finally crumbling under the weight of his private one, brought home in a scene where Jimmy suffers a brief psychological break as he rambles on and on, collapsing on live TV, a wrenching evocation of a man who emotionally no longer has any place left to hide.

Philip Baker Hall died on Sunday June 12, 2022. He was 90.

No comments:

Post a Comment