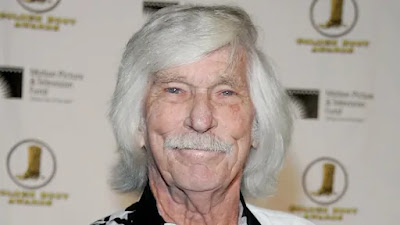

L.Q. Jones was born Justus McQueen, a transition from real name to screen name that, frankly, feels backwards, like Cary Grant going to Archibald Leach rather than vice-versa. McQueen’s stage name, though, doubled as the name of his very first character onscreen, Private L.Q. Jones in Raoul Walsh’s “Battle Cry” (1955). And even if Jones implied in a 2017 interview with Nick Thomas that the studio proposed this name change, it proved pertinent, a burgeoning actor so custom-built for Hollywood that the person just sort of merged with the first persona he played. The long white mane his hair grew into later in life was distinct, his voice was even more distinct, a laconic drawl born of his Texas heritage that seemed to suggest he was both permanently in the process of going hoarse and in a perpetual state of wry amusement with life. That voice made him perfect for an assortment of roles in westerns, both on TV and in the movies, including some of the most seminal films of the genre, “Ride the High Country” (1962) and “The Wild Bunch” (1969).

He was also featured in a crucial supporting part in Martin Scorsese’s “Casino” (1995), which was less a spiritual sequel to “Goodfellas” than Grandmaster Marty’s version of a western, Las Vegas as the mafia’s Manifest Destiny, running afoul of the settlers who have already set up shop and staked their claim. Those settlers are represented by County Commissioner Pat Webb, played by Jones, who asks a favor of Tangiers top dog Sam “Ace” Rothstein (Robert DeNiro). If Webb refers to himself as a “poor old civil servant,” the way Jones says the line reveals its weaponized self-effacement, a man here to draw the line in the sand in one of Scorsese’s most elegantly composed scenes.

Scorsese and this editor Thelma Schoonmaker introduce us to Webb with the camera looking over his shoulder as he peers down at Sam’s secretary (Linda Perri), echoing the casino eye in the sky that Sam references earlier, the county commissioner omniscient in a way superseding even the preeminence of organized crime. Sam briefly stalls, a comic moment in which he just needs time to put on his pants, echoing Leonard Bernstein’s old conductor’s trick about keeping your slacks looking sharp, which definitely seems like a trick Ace would have up his sleeve.

As he does, Marty and Thelma then cut back to Webb, now seen in long shot, standing just outside the door and sort of hitching up his pants, looking in his costuming and countenance for all the world like an old west cowboy fingering his six-shooter before a gunfight. Yet, when Sam’s secretary asks if Webb might like anything, he replies “No thank you, little lady.” The term might be condescending in and of itself, but Jones renders Webb’s air as convivial, epitomizing how he occupies both plains at once.

Once Webb is inside Sam’s office, Scorsese lingers on a shot of the men’s shoes, which is not mere Tarantino foot fetishism but a nifty underlining of their identities, their respective communities, and how they differ.

That is further underlined when they finally sit down across from one another, Sam upright, Webb reclined, relaxed. Their conversation, it’s about Webb’s brother-in-law Don Ward, who Sam has fired for incompetence (and who this blog has previously compared to Don Jr.) and Webb is hoping to get reinstated since “family and money votes.” Inherently, it’s a funny conversation, illuminating too, not just Webb seeing how many casual threats he can make but Webb admitting his brother-in-law is as dumb as Sam says he is and so what, politics rendered as a protection racket for dummies, which in a sense makes Sam right and Webb wrong even if Sam is also wrong because he can’t quite see that he’s signing his own metaphorical death sentence by refusing to acquiesce.

The metaphorical death sentence is issued in the final handshake, the camera looking up at Webb, this time, rather than over his shoulder, transforming Jones’s impassive expression into menace.

It’s a sign of how Jones knew how to let the camera do the work, which he does again later in the courtroom scene when Ace’s crucial gaming license application is denied in a split-second. There are backroom dealings, of course, facilitated by Webb that cause this to happen, though we never see them, because we don’t need to. No, we just see Webb, in this shot, glancing up at Rothstein, one frame in which he does not even speak and yet we understand he has orchestrated everything.

It was a beautiful, rich irony that Robert Altman’s last movie, “A Prairie Home Companion” (2006), was one specifically about mortality, with an angel of death (Virginia Madsen) the credits deem a Dangerous Woman hovering in the wings of a variety show on its last night. “Every show is my last show,” declares the program’s host (Garrison Keillor). “That’s my philosophy.” “Thank you, Plato,” replies one of the evening’s performers, Rhonda Johnson (Lily Tomlin). “Kierkegaard.” It’s Altman offering up wisdom in the face of kicking the bucket and then laughing at it, the movie’s myriad musical performances spiritually defying the program’s end just as the movie spiritually defies Altman’s own. It’s not bitter, “A Prairie Home Companion,” not in the slightest, just bittersweet, which Madsen embodies in her dexterous performance.

We come to grasp who she is when she stands backstage alongside Chuck Akers (Jones), about to go on stage. We can see her, but he can’t, and when she touches him, Jones effects the sensation of some unexplainable sensation in his body, someone’s who countdown to the end has just begun but doesn’t know it. He walks out from the wings and to the microphone, Jones’s very air imparting that of his character, one who has been around a long time and seen it all, and as he begins his song, Altman cuts to a shot of the Dangerous Woman, a wistful smile on her face, watching him for a moment and then turning and walking away to her left, the camera following for a brief moment, that movement mystically embodying the feeling of a life passing before our eyes and transforming Chuck’s song – The Carter Family’s “You’ve Been a Friend to Me” – into an unwitting eulogy.

In a way, it became Jones’s unwitting eulogy too, at least as far as the movies went, given “A Prairie Home Companion,” echoing Altman, wound up being his final screen role, sixteen years ago, before passing away on July 9th at the age of 94. Every movie is your last movie.

No comments:

Post a Comment