The more Oscar bait-y Hollywood musical biopics often like to equate their subjects with superheroes by giving them origin stories to match, a trope spoofed in the recent Weird Al biopic by way of his glowing Hawaiian shirt. Spoofing, though, is not what Luhrmann does; he goes a hundred and fifty miles an hour in the other direction. Here he makes the superhero origin literal (in a figurative) sense by showing the young Presley reading Captain Marvel Jr. comic books, wearing a yellow lightning bolt around his neck to fashion himself in the image of his own hero, and using bombastic visual language to render the character’s lightning bolt moment. That lightning bolt moment occurs when the young Presley enters a Pentecostal revival tent immediately after peeking into a juke joint where Arthur Crudup (Gary Clark Jr.) is playing “That’s All Right, Mama.” Though it comes close to advancing the idea of Elvis full-on appropriating African American music, it evades this charge in how Luhrmann brings to life the sudden manifestation of the future King’s essential musical nature as marrying the secular and the spiritual, Rock ‘n’ Roll as religious experience.

True, the country music that also inspired Presley is virtually absent aside from the overly amiable Hank Snow (David Wenham), and in showing famed black performers as something akin to Elvis’s sherpas he risks reducing them in ways he does not intend. But Luhrmann also shows Elvis watching a Little Richard performance, as adrenalized as Presley’s own, wishing he could perform that same song, emphasizing how the music industry worked for whites and how it worked for blacks. In Luhrmann’s telling, Elvis is positioned in the way Public Enemy’s Chuck D saw him years later through the lens of “Fight the Power”: not necessarily as the racist the lyrics overtly say, but as a sin eater for the whole industry, one who capitalized, rightly or wrongly, on the industry’s all-encompassing racism.

“Elvis” is at its best, though, not when considering its subject through the prism of time but in opening an ineffable portal to the past. If these musical biopics are so often rendered as mere wax museums with a pulse, to quote Vincent Vega, Luhrmann succeeds by making Elvis come alive, to feel the way he must have felt then, to put us in the room with him, so to speak. It’s not so much Austin Butler’s singing, which has been reported as a mix between Butler’s own voice and Elvis’s recordings, but his movement and how Luhrmann and his editors Jonathan Redmond and Matt Villa evoke the communion between Presley and his audiences.

That is never more apparent than Presley’s appearance on the Louisiana Hayride show, where the channel he opens up to his audience is palpable, plugging us into the same figurative electrical socket as all his ravished fans, the involuntary shrieks from the women incredibly, electrically, illicitly disappearing the line between shouting in church and shouting during sex. The “Take My Hand” scene from “Walk Hard” took the piss out of what constituted so-called Devil’s Music, but in this scene “Elvis” puts all the piss back in. Presley’s celebrated 1968 comeback special, meanwhile, is composed as much like a suspenseful action sequence as a musical performance giving great life to the idea of his career and legacy being on the line while Luhrmann deftly employs flashbacks and split screens for Elvis’s inaugural show at the International Hotel in Las Vegas to epitomize it as a synthesis of everything he was even as it sets up as the final nail in his coffin. And we see the Rock ‘n’ Roller’s famous appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1957 partly through a living room television, one that seems to glow, illuminating a King fit for his crown over the airwaves.

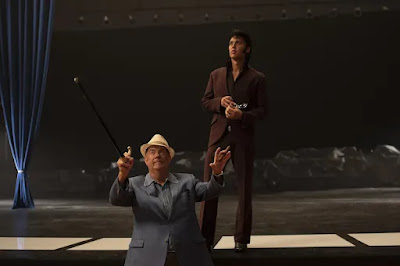

Paradoxically, in a movie of excess, the scenes of excess, of drinking and drugs and his failing marriage to Priscilla Presley (Olivia DeJonge), lag as much as Elvis falters in his own life, offering no real insight, Luhrmann’s own aesthetic extravagance here just doubling back on itself to ultimately feel as empty and rote as any behind the scenes Rock ‘n’ Roll drama. Despite all this, what rescues the movie is that Col. Parker framing device, which both implicates the audience in Elvis’s public pressures and emotional downfall while also evoking the sensation of Elvis being trapped in an emotional prison. If Butler is not necessarily finding anything new in his character’s tragic slide toward the end, he doesn’t need to, Elvis itself evincing the sensation of the Rock ‘n’ Roll raging against the dying of his own light. Luhrmann, though, doesn’t just leave it there. If biographical movies often conclude with footage of the real subject with no conception of that footage beyond an honorary parenthetical of the real person, Butler’s Elvis suddenly gives way to the real one, a transition emphasizing Presley’s voice, and how despite everything, it could still break free.

No comments:

Post a Comment