“Barbie” begins with an ingenious parody of the beginning to “2001: Space Odyssey” by reimagining an ape smashing a bone to evoke The Dawn of Man by having several little girls smash outmoded baby dolls as Barbie looms over them to evoke how Gerwig is both smashing the idea once so hilariously satirized by The Onion that mass market entertainment and feminism cannot co-exist while also illuminating how Barbie gave little girls permission to dream of themselves in terms beyond motherhood. Of course, when the sequence’s narrator (Helen Mirren) notes how this realization cured all ills, her cheeky tone lets us know this isn’t true, setting up “Barbie” as taking place at the intersection of paradise and reality, site of eternal struggle.

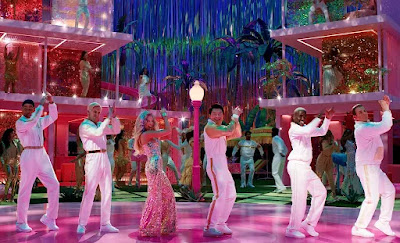

Margot Robbie stars as Barbie, though not the Barbie, even if she is referred to as Stereotypical Barbie, but one of many Barbies, all the different models of Mattel’s chief commodity through the years, even the discontinued ones, living and working in a place called Barbieland. Gerwig and co-writer Noah Baumbach imagine Barbieland as a kind of perpetual movie musical, the Barbies waking up by singing and ending the day with disco dance parties, while Ken (Ryan Gosling) only exists in the context of Barbie, as if at the end of each night he gets put back up on an invisible hook until Barbie wakes up again. It is a fuchsia infused female utopia without pesky subtext, underlined in the comically literal dialogue, if ominously so, portended by the imaginary milk Barbie drinks and the fake waffles she eats. Life in plastic, to paraphrase Aqua, it’s fantastic, until it’s not, which occurs during one of those dance parties when Barbie suddenly wonders if anyone else thinks about death, triggering an age-old journey of self-discovery.

Endlessly inventive, Gerwig utilizes Barbie’s myriad history and characteristics, like a recurring joke involving the doll’s flat feet, to dissect their deeper meaning by turning them inside-out. She goes even further by embedding the innate anti-feminism of Barbie into the plot by rendering it so that all Barbies in Barbieland are essentially manifestations of the little girls playing with them in the real world, meaning Stereotypical Barbie exists as a kind of reflection of the societal perfection expected in women. So-called Weird Barbie (an impeccably cast Kate McKinnon), whose real-world counterpart has fashioned her as being eternally in the splits, her very existence a rebellion against such perfectionism, explains that Barbie’s fears can only be quelled by traveling to the real world and finding the person playing with her. Desperate to prove himself, Ken tags along.

The cold hues of actual reality cast Barbie’s omnipresent pink in a whole new light, transforming her into a confused and complicated individual, a figure to be objectified but also a person who in one scene with the Mattel execs trying to wrangle her literally refuses to be put in a box. At one point, Barbie sits on a bench next to an older woman, and Gerwig frames them as virtual reflections of one another, quietly kicking the notion that women cease to exist in the eyes of society at a certain age square in the teeth. Ken, meanwhile, becomes less a fish out of water than a duck taking to it, discovering the concept of patriarchy and bringing it back to Barbieland to calamitous effect, his vision for a new world order manifested in a hysterical montage that’s like an Esquire-produced version of the recruitment video in “The Parallax View.”

It is tempting to decree that Gosling steals the movie, so amusing is he, playing a kind of Cobra Kai instructor in an MGM-ish musical, all vain if clueless swagger, so desperate not to appear ridiculous, he comes across that much more ridiculous, ultimately as fragile as, well, a doll. But “Barbie” belongs to Robbie. For one thing, it’s an astonishing physical turn, embodying the rigid movement of a plastic doll to great comic effect. What she does in a mid-movie chase scene, I’m not sure I can even explain, evincing a loose-limbed slow-motion recounted by the camera in real time, as close to a real-life Looney Tune as I can recall. Yet, delicately and incrementally she lets dollops of humanity seep in, especially in her smile, progressing from frozen solid to shining it on to something real and wondering, her whole turn eventually landing at the same nexus as the movie. As it concludes, it becomes almost too talkative because what needs to be said is being conveyed entirely by Robbie, the drama of her impending leap of faith playing out right on her face, so that you can virtually see the moment when Barbie passes into being a human - strike that - a woman.

No comments:

Post a Comment