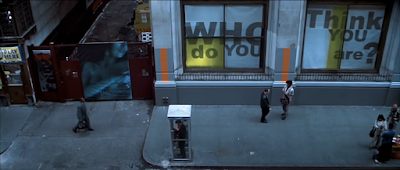

Alfred Hitchcock knew the dramatic value of a good phone booth, trapping Tippi Hedren in one when “The Birds” attack, a more terrifying precursor to The Beatles deftly employing phone booths as a hiding spot one year later in “A Hard Day’s Night.” Indeed, it was around this time that producer Larry Cohen pitched the Master of Suspense the idea of a movie set entirely within a phone booth. Yet, if Hitchcock had managed to wrangle an entire movie of people in a “Lifeboat,” he and Cohen could not devise a whole film around an enclosed pay phone, and it was not until the late 90s, near the peak of public pay phones in the United States in 1995, that Cohen figured out his idea and began selling the script. And then Hollywood rigmarole, with directors and actors coming and going, meant that by the time “Phone Booth” at long last reached the big screen for a proper release in the spring of 2003, public pay phones were ironically on their way out. This looming extinction is baked into the script, with the phone booth where Colin Farrell’s character is trapped courtesy of a sniper’s rifle cited as being the last one in New York and scheduled for removal. It functioned as a spiritual goodbye, of sorts, as the very next year, 2004, Chris Evans starred in the appropriately titled thriller “Cellular,” where his unsuspecting character fields a mobile call from a woman (Kim Basinger) who desperately needs his help.

In retrospect, these two movies signaled a demarcation in movie land between analog and digital that mirrored the evolving nature of real life where the omnipresence of cellular phones inexorably squeezed out pay phones, leading to one portion of the plot of “Phone Booth” finally coming true as New York’s last street payphone was removed in May. If the pervasiveness of cellular technology has yielded convenience, and all the standard bullet point benefits, it has caused us to lose something too. In appraising for The New York Times how pay phones and phone booths cordoned off “telecommunications…to discrete spaces, separate from the rest of your life,” Melissa Kirsch referenced Richard Dreyfuss’s call to Marsha Mason from a phone booth in a thunderstorm in “The Goodbye Girl.” Twenty-eight years later when Drew Baylor called Claire Colburn in “Elizabethtown,” they could drive to a physical meet up while still chatting via their 2005-appropriate block phones, evoking how that wall of separation had crumbled. As a character, Claire has taken all sorts of flack over the years, and fair enough, but when she dryly laments “we peaked on the phone,” woah nelly, was she was foreshadowing our present.

But if that means “Phone Booth” was in many ways a culmination of phone booths and pay phones at the cinema, it has never quite felt to me as their emblematic movie apex, too much of a gimmick to truly capture the essence of Alexander Graham’s Bell invention in a public space. That’s why Dirty Harry (Clint Eastwood) running around to answer calls from pay phones doesn’t move the needle for me just as John McClane (Bruce Willis) doing it however many years later in “Die Hard With a Vengeance” feels the same. No, the ultimate “Die Hard” pay phone moment for me will always be from the second “Die Hard,” “Die Harder,” when John McClane is waiting for his wife at Dulles and she calls his beeper (!) from her airphone (!!) and to call her back he has to wait for a pay phone (!!!) to open up in a crowded airport on Christmas Eve. It’s this mini-little moment of drama that Bruce Willis plays to the subtle hilt, diving for a pay phone that suddenly opens up like a running back hitting the hole, the camera catching sight of the disappointed patron who missed his shot to make his own call, as Willis indulges in this little moment of victorious pleasure while dialing, his body language reveling in having this pay phone all to himself, a tiny private space carved out of the mass of Dulles.

Essentially, of course, that’s what a phone booth could provide, contrary to what “Phone Booth” would have you believe, a sense of privacy, an intimate space, where Ritchie Valens serenaded the Donna in “La Bamba” and Clarence and Alabama, indifferent to the whoosh of semi-trucks flying by, get it on in “True Romance.” Of course, that intimacy can swing both ways, entrapping you, whether it’s Lloyd Dobler on the phone in the rain or Jimmy Conway in “Goodfellas.” “Anchorman” Ron Burgundy might have memorably bellowed that he was “trapped in glass case of emotion!” but no one was ever more trapped in an emotional glass case with greater intensity than Jimmy Conway in “Goodfellas.” You remember the moment, I’m sure, him learning via pay phone that Tommy has been whacked the very day he was set to become a made man and then Jimmy taking out all his frustration on the phone booth, battering it and kicking it with such ferocity that the street corner edifice tumbles. Once I saw Anne Heche on the Late Show with David Letterman to promote “Wag the Dog” and the clip they played was one on the plane when Heche is talking with a sleep mask-wearing DeNiro. Letterman jokingly said something to the effect of, That guy is such a good actor, he can act blindfolded. Well, DeNiro was such a good actor, he could turn a phone booth into a scene partner.

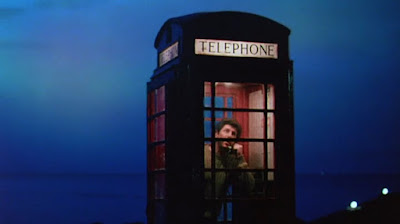

True, phone booths became a symbol of blight, the word served up by The New York Times in going over the last pay phones in NYC, one frequently coded with racial prejudice. 1980s movie like “The Secret of My Success” pseudo-comically demonstrated the terrors of the Big City by trapping Michael J. Fox in a phone booth as a shootout erupted around him, while Penelope Ann Miller being trapped in a phone booth in a Chicago bus station in “Adventures in Babysitting” was less a haven than emblem of scary downtown Chicago to a cowering suburbanite. Even so, movies of the same era were just as likely to treat the phone booth with reverence. They are where Clark Kent changed clothes, after all, and one served as a time machine for “Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure.” As great as the last one was, though, no phone booth ever served as more of a portal than the red telephone box in “Local Hero” (1983). That’s where oil and gas exec Mac (Peter Riegert) gets dispatched to Scotland to see about acquiring a Highlands village for a refinery. The company’s owner, though, Felix Happer (Burt Lancaster), in a twist more fanciful than any ancient fairytale, is a CEO less interested in profit than stargazing. In one scene he listens on the other end of the phone from Houston as Mac stands in that phone box and describes the sky. The pay phone becomes a kind of portal, the sequence improbably rendering Reach Out and Touch Someone as something more than mere marketing verbiage, nearly peak payphone at the movies but not quite.

In a sense, Paul Thomas Anderson’s “Punch-Drunk Love” is a movie all about phones. It begins with novelty plunger salesman Barry Egan (Adam Sandler) taking the name and extension of the customer service rep on the other end of his phone line and that scene gives way to Barry trying to give his home phone number to one of his own clients on a different call. Both of these telephone-based conversations evoke Barry’s loneliness as much as the wide angles in which PTA frames him, and that loneliness becomes only more acute when at home he dials a phone sex hotline, the meekness in Sandler’s turning Reach Out and Touch Someone into something else altogether. Of course, this hotline reveals itself as a blackmail scheme, a personalized kind of robocall, betraying the phone as a familiar and ongoing tool of cruddy capitalism, while Barry’s profane over-the-phone face/off with the company’s owner (Philip Seymour Hoffman) demonstrates the phone as a weapon, a source of intimidation, as much as Christopher Plummer gazing up from that phone booth and into Elliot Gould’s apartment in “The Silent Partner.”

“Punch-Drunk Love’s” most critical scene doubles as the most important phone call Barry makes, after deciding on a whim to fly to Hawaii to see the woman he loves, Lena (Emily Watson), only calling her once he has arrived on Oahu. The scene, it’s pure romance, the pay phone noticeably lighting up when Lena answers. But once he’s told her he’s there and she tells him to come meet her, he starts asking her questions, the kind you might on first date, comically ignoring her pleas to hang up by just posing another getting-to-know-you query instead. In Kirsch’s piece for The New York Times, she notes that even if her beloved phone call in “The Goodbye Girl” is sentimental, it can be a useful metaphor for delineating boundaries between virtual and real life, and that is essentially what Anderson is evoking here even as he takes it one step further.

Barry just wants to stay on the phone, where things seem a little easier; Lena is telling him to hang up and come join her in the real world.

No comments:

Post a Comment