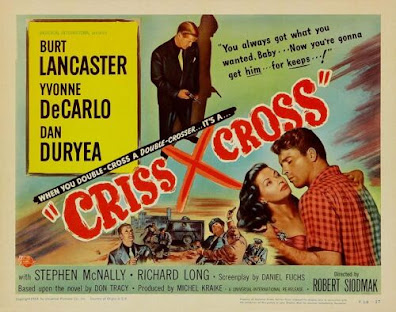

Fate is typically noir’s foremost element, laying its dreaming or scheming characters low, regressing to the mean of a cruel, cruel world. It’s a cruel, cruel world in Robert Siodmak’s “Criss Cross” too, its plainly named protagonist Steve Thompson (Burt Lancaster) robbing the very armored car he drives to try and flee for greener pastures with his ex-wife Anna (Yvonne De Carlo). It goes about as well as you’d expect. The heist, though, pulled in tandem with Anna’s gangster husband Slim Dundee (Dan Duryea) feels less important to the flashback-heavy, hopscotching narrative than the way director Robert Siodmak and screenwriter Daniel Fuchs, working from a 1934 novel by Don Tracy, deconstruct the pull of fate. Back home in Los Angeles after wandering across the country in the wake of his divorce, Steve repeatedly tells us in voiceover that he hasn’t returned home to see Anna even as he seeks out their old haunts. And when he employs an analogy about getting cellophane stuck in one’s teeth to extract the apple that’s already stuck in one’s teeth, it sounds like nothing more than a daft man trying to write off his own daft actions as destiny.

Steve is that classic archetype of film noir, a sap, and it says something that the muscular, 6’2” Lancaster can so convincingly play one. The way his hair is styled in the very first scene, an illicit parking lot rendezvous with Anna makes him look younger, smaller, and Lancaster’s line readings alternate between clueless and persecuted. “You’ve got it all figured,” he says to his police buddy who’s only looking out for him that lets you know Steve hasn’t figured anything. His impending doom is magnificently amplified by De Carlo, a pantheon Femme Fatale, swooningly playful in demonstrating how Anna wraps Steve right around her finger and savage in how she reduces Steve to just a dumb box of rocks in the ultimate double cross, a turnabout made that much more painful by Lancaster’s virtual puppy dog helplessness.

De Carlo’s introduction is a dance duet (opposite an uncredited Tony Curtis) that Siodmak lingers over, a sizzling historical rebuttal to our pitifully chaste cinematic present, leaving you as smitten with her as Steve is while watching her from off to the side, a fish putting the hook in his own lip if there ever was one. It’s nearly as voyeuristic as that beginning parking lot rendezvous opening scene where, for a moment, De Carlo seems to look past Lancaster and right into the camera. I gasped. Like Steve, she’s got you.

No comments:

Post a Comment