Kirsten Dunst in "Wag the Dog"

as Tracy Lime

It’s the image we remember, which is the whole point since the characters in the film are specifically crafting a false image to provide evidence of a war that doesn’t actually exist. So we remember her as the phony Albanian refugee fleeing the phony reprisals with the phony Calico kitten in tow as the phony Anne Frank sirens wail. Do we remember that her name was Tracy? Do we remember that she was played by Kirsten Dunst? Do we remember in a film that has roughly 775 lines of pure comic gold she might have delivered the single best one?

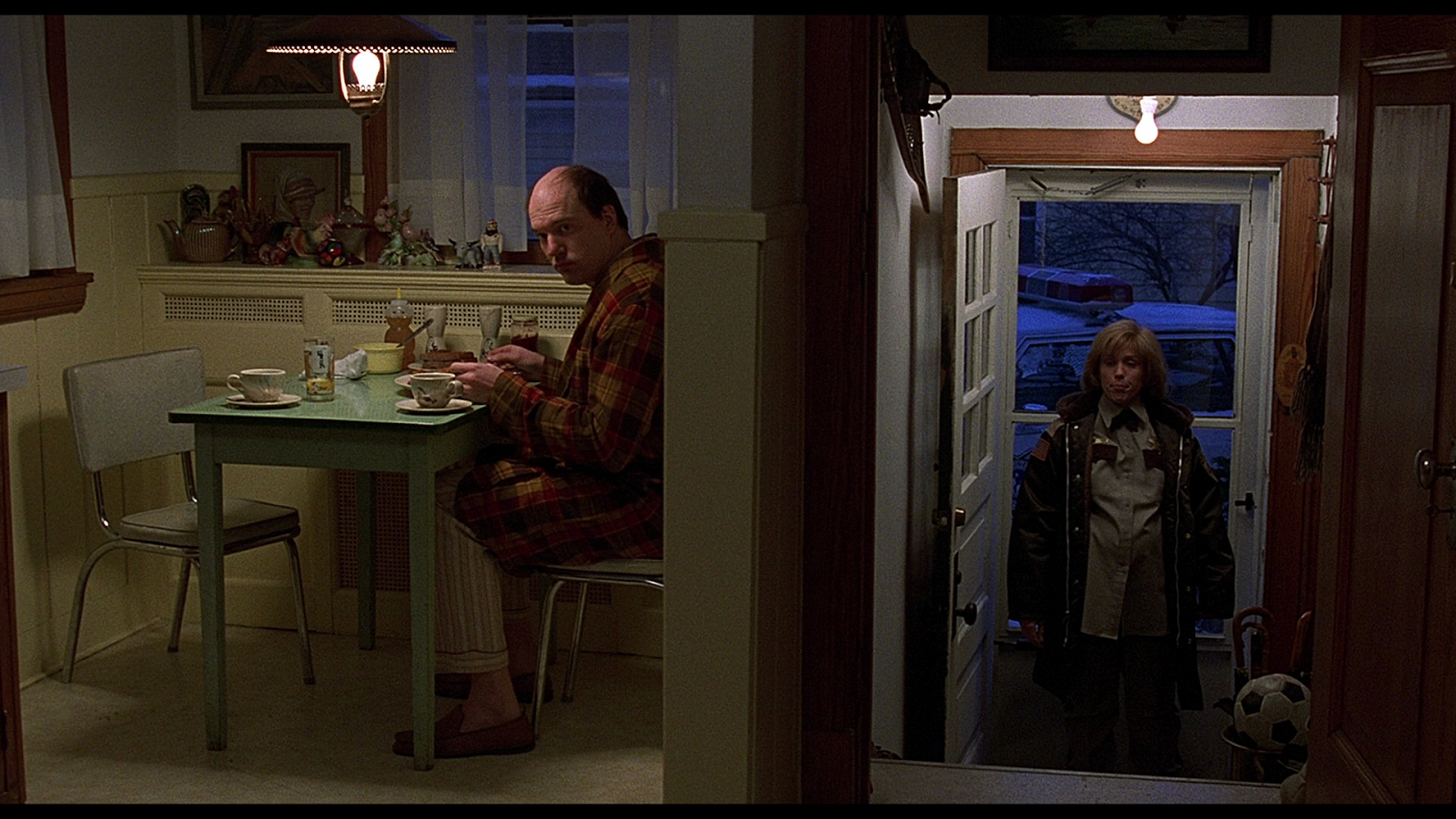

There is a moment early in the film when White House Spin Doctors Conrad Brean (Robert DeNiro) and Winifred Ames (Anne Heche) have sought out Hollywood producer Stanley Motts (Dustin Hoffman, riffing on Robert Evans but still crafting a wholly original character) for aid in staging the phony war that will distract the American people from a Presidential scandal a couple weeks ahead of the ensuing Presidential election. To prove they have the White House’s ear, Conrad and Winifred dial up an aid in the midst of a televised West Wing press conference and Stanley feeds him lines. The aide repeats them word-for-word but Stanley is unimpressed. “He didn't phrase it right. He didn't sell the line.”

Well, how do you sell your walk-on/walk-off performance amidst Dustin freaking Hoffman and Robert freaking DeNiro? As Tracy Lime (lime, the critical garnish to the cocktail), Dunst plays her as a genial if in-over-her-head and pointedly young struggling L.A. wannabe starlet. She knows enough to know she shouldn’t be signing something without her agent’s consent, but she also knows she wants to pad that resume. And when she asks Conrad, smiling sweetly, about that very thing, he advises she can’t tell anyone that she ever did this. “Is it a guild thing?” she wonders earnestly. “They can come to your house and kill you,” he says, still smiling sweetly. She turns away while simultaneously being doused with makeup and Dunst’s expression says it all – not fear, not at all, but confusion.

That confusion is underscored by what she's carrying in her arms. Moments earlier, in lieu of the kitten she was told she’d be getting to hold, into her arms is plunked a bag of tortilla chips. Her response is matchless, possibly's the film's funniest three words, though the delivery of the words is specifically what makes them so funny. She says: “These are chips.” And she sells the line. She sells it. She sells it precisely because she isn’t selling it – she’s just saying it. She was told she would be holding a cat and well, hey, these? These are chips. So she asks about the cat. “We’ll punch it in later,” she’s told. “You’ll punch it in?” she asks, not entirely up to date on post-production lingo. And that's the last we hear from Tracy, aside from the souped-up news report casting her as a war refugee, just another actress nobody knows left to wander around haplessly in the green screen wilderness.

I imagine Daisy Ridley showing up for her first day of “Star Wars: Episode VII” filming and being told she will be wearing a sort of exotic traditional Alderaanian headdress only to have J.J. Abrams nix all headdress choices and then some intern plunks a pot roast on top of poor Daisy's head and tells her they'll just punch in the headdress later.