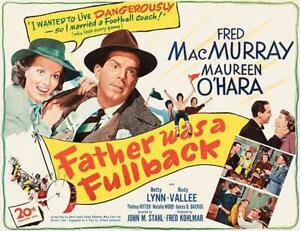

“Father Was a Fullback” achieves a rare trifecta: it is a movie based on a play that feels like a sitcom. It is about a college football coach, George Cooper (Fred MacMurray), navigating both job pressure and pressure at home. And though the collision of his flailing character with so many others and the complications these collisions engenders all suggest a fast-moving screwball movie, director John Stahl dials down the pace and tone to such a degree that you can actually detect where the movie has its characters pause for laughs which for me, watching alone, never arrived. Where’s the laugh track when you need it? I kept imagining myself as Russell Dalrymple, President of NBC, expeditiously passing. What’s worse, rather than surreptitiously functioning as a screwball social commentary a la, say, My Man Godfrey“, “Father Was a Fullback” just sort of turns to sentimentalized stone, its sitcom aesthetic presaging the the golden age of American televised situation comedies and the Eisenhower Era values they often espoused more than tore apart.

“Father Was a Fullback” opens with George, head coach at State U., losing yet another game in a winless season. The administration and the alumni are hot on his heels and, if you adjusted the tone here just slightly, the way MacMurray has Coop mope around would truly suggest living as a college football coach comes with an anchor permanently affixed to your neck. He gets calls at home from furious fans and helpful hints about what trick plays he might run to turn the tide. The latter seems poised to factor in as a crucial plot point, though no matter the emergent sentimentality, there is still a little truth tucked in here, about how boosters run these mini-empires more than coaches and how coaches depend more on recruits than schemes. Indeed, when Coop gives a speech to the boosters, he sort of unsubtly lays blame at the feet of the players; he doesn’t have “the material” he says, epitomizing the sport as an arms race for talent.

Still, the Sunday morning after a game Coop is not holed up in the film room, he’s at church, suggesting “Father Was a Fullback’s” overriding wholesomeness. And the living room of his home is the main place of action here more than the locker room as he navigates having two mismatched daughters and a maid (Thelma Ritter) who is literally betting against his team. As Coop’s wife, Maureen O’Hara is mostly called upon to just play semi-harried rock of the family and Ritter, so acerbic and so alive in so many roles, is sadly reduced to a more subdued Alice Nelson despite her gambling predilection. Natalie Wood, at least, brings a little energy as younger daughter Ellen, Margaret O’Brien’s Tootie in “Meet Me in St. Louis” with a little Gaby Hoffmann in “Sleepless in Seattle”, her character deftly playing parents against big sister and vice-versa and getting a kick out of it, so much so that I briefly let myself imagine the whole movie through her eyes. Her big sister, though, Connie (Betty Lynn), proves the movie’s key character, boy crazy and sort of played that way almost literally by Lynn, her father’s misguided attempt to manufacture a date for her yielding the big twist.

Recently there was a real world scandal, of sorts, in which Jacksonville Jaguars head coach Urban Meyer was caught on camera, ah, shall we say, cavorting on the edge of a dance floor with a woman who was objectively not his wife. In a vacuum, this might not matter, something between a husband and his wife and his family, no more. Ah, but Mr. Meyer is the same man who, at the 2011 press conference naming him Ohio State football coach, revealed the quote-unquote contract his family made him sign to not neglect his duties at home upon choosing to accept the job. Why just a few weeks ago a segment for a Jacksonville TV station at the Meyer home revealed a living room coffee table weighed down with framed family photos, looking less like any actual person’s home than an exaggerated endeavor to demonstrate himself as a Family Man. Really, it should not matter to us whether Meyer is a family man but it has long been de rigueur for football coaches to publicly present themselves as Family Men nonetheless, mirroring the familiar cliche of football teams as families. And if the historian Murray Sperber has credibly argued how Golden Age movies like “Knute Rockne, All American” helped solidify the cult of the football coach, perhaps “Father Was a Fullback” did the same for the hackneyed notion of football coaches as family men, brought home in Connie’s falling in love with the nation’s primo football recruit and he with her, ensuring he signs with her Dad’s State U., leaving all barriers between team and family erased.